Eliane Woxixaki, leader of the Waiwai women’s association, brought her yellow feathered headdress on the trip to Sweden, and there is an almost identical ornament in the collection.

The development of the Tainacan Project at the Brazilian Institute for Museums (IBRAM), along with its president Fernanda Castro’s focus on enhancing the Institute’s capacity to independently manage its digital strategy, opens up new possibilities for Brazilian museums. As they confront old challenges with updated tools, they’re adapting their approaches and broadening its channels to connect with both new and existing players in the memory and heritage sectors. This includes embracing new dynamics in social media and exploring methods for remote digital engagement.

Earlier this month, Professor Dalton Martins, General Coordinator of Museal Systems at IBRAM, traveled to Gothenburg, Sweden, to continue his research collaboration with the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Gothenburg, in partnership with the Federal University of Western Pará (UFOPA) in Brazil and the “Museum of World Culture” in Gothenburg. This distinctive museum was established by the government as part of a dialogue on the self-identity of Swedish society, and has become a focal point for public discussions*.

The present research collaboration focuses on “decolonizing ethnographic databases,” which emerged from discussions about “digital repatriation of collections” in Europe after the 2018 fire at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro. It’s worth noting the longstanding relationship between the “Museum für Völkerkunde” in Berlin and the “Göteborgs Museum” in Gothenburg with the Museu Nacional and other Brazilian institutions since the 1880s. They actively exchanged objects for major exhibitions, contributing to the scientific exchange of knowledge through collection sharing**.

The research project is conducted by the University of Gothenburg in collaboration with the Museum of World Culture and the Federal University of Western Pará (UFOPA). In 2022, the first group from the Amazon, the Waiwai, arrived. After a long journey from the rainforest to Sweden, they were able to see objects over 100 years old that are part of their cultural heritage.

In 2021, the Brazilian Institute for Museums joined the project, coinciding with the University of Gothenburg receiving funding from the “Europeana Research Grants Programme***.” This development prompted a report that identified the Tainacan digital repository—a free software (WordPress plugin) developed and maintained by Brazilian public universities with support from IBRAM—as an appropriate tool for offering technological assistance in the decolonization of ethnographic databases.

In 2022, the project’s inaugural mission brought members of the Waiwai ethnic group from Brazil to visit the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden. The visit centered on items related to Brazilian indigenous peoples, specifically their own tribe****. These objects were collected in 1925, and there’s limited information about them. For the Waiwai people, identifying these objects and helping organize the collection is significant for various reasons. “Many of the items are still being made today,” explains João Kaiuri, a Waiwai spokesperson.

During the mission in Sweden this month (Mar/2024), Palikur representatives conducted the identification of their objects, following a similar process to what the Waiwai did in 2022. Brazilian and European researchers discussed the operational design and technical features for structuring methods and practices of decolonizing collections, drawing from their experience with Brazilian groups. The goal is to create a framework for digitally sharing museum cultural heritage collections with indigenous communities, proposing methodologies and practices that can be applied to other collections and contexts as well.

Innovation creates new avenues of action for museums.

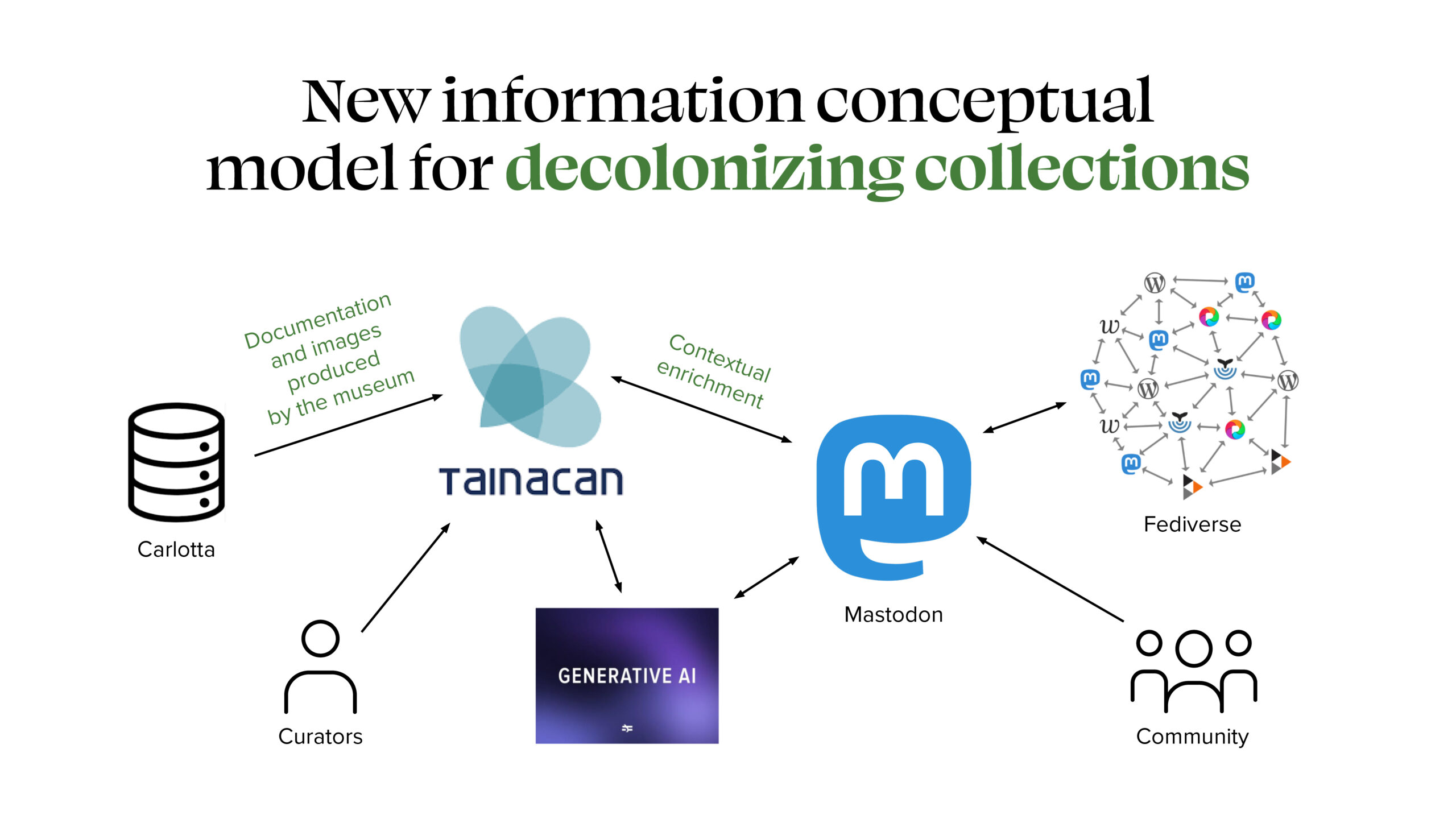

Professor Dalton Martins’s participation in the mission highlights the strong comimitment of IBRAM and Brazil in developing innovative solutions for the museum field and digital collections, particularly regarding decolonizing collections. This advancement explores new opportunities for museums and specialists in memory institutions to facilitate dialogues around collections, similar to curating networked conversations. The recent experimentation of the Brasiliana Museums project with the Fediverse, along with the opportunity to explore active remote participation in online museological processes, supports the proposed conceptual model that Ibram is currently presenting to its European partners, as illustrated in the diagram below.

The design of the conceptual model illustrates the partnership plan, which involves creating pilot projects to train representatives of ethnic communities collaborating with the “Museum of World Culture” in Gothenburg—specifically, the Waiwai, Palikur, Munduruku, and Ticuna. The potential of AI and Machine Learning functionalities can easily be integrated into Tainacan because of its WordPress plugin architecture, allowing for the dynamic translation of textual items from collections into the proposed workflow. Additionally, the potential of the Fediverse can be used to connect curator teams and groups of interested researchers. Prof. Dalton Martins highlights the aspect that caught the researchers’ attention during the presentation of the conceptual model.

“…the design illustrates the transition in the museum’s role, shifting from being the sole authority on collection truths. In its new role as a facilitator of dialogue on memory, heritage, and collections, the museum creates a conducive environment for open, transparent, and well-documented discussions.”

Dalton Martins

From our perspective at IBRAM in Brazil, we envision the ActivityPub protocol as a chance for memory institutions to utilize social network-like infrastructures for projects involving digital cultural heritage. This could potentially shift some control over the governance of digital environments, currently dominated by BigTech companies, back to institutions historically responsible for documenting and preserving culture for future generations.

Back in Brazil, Dalton tells us that during his visit to Leiden University in the Netherlands, following the meeting with the Palikur in Gothenburg, Sweden, he connected with local experts closely monitoring the technological solutions for digital cultural heritage in Europe. His colleagues wanted to talk about the innovations incorporated into the proposed model for decolonizing collections based on the open-source Tainacan software.

“In conversation with colleagues about Europeana, we’ve observed that the primary challenge in evolving the process of aggregating cultural heritage collections is ensuring the quality of metadata from the integrated collections in their respective institutions. The plan to provide aggregation partners with integrated tools to support metadata enrichment, and to use the ActivityPub protocol in Tainacan to document dialogue with specific audiences, has proven to be an appealing proposal.”

Dalton Martins

Cultural heritage projects that involve direct collaboration / participation from the public are widespread in Europe. In Estonia, the submission of digital images by citizens is a common method for receiving/collecting new collections. These initiatives serve to enhance the museum’s visibility, attracting new audiences, and deepening the connection with its user community. By actively involving the public in the preservation and documentation of cultural heritage, museums foster a sense of ownership and engagement among their visitors, ultimately enriching the overall cultural experience for everyone involved.

In this case as well, the creation of descriptions for items in the process of documenting the collection gathered from the public ceases to be the sole task of the museum expert. The process of “inclusive documentation” proposed by the initiative in Estonia integrates external information-gathering activities into the museum workflow. It begins with (1) Collection (items and information from the external public), continues with (2) Cataloging (by museum staff), and moves on to (3) Research and Additional Descriptions, a stage that can organize, correct, and supplement information about the items, comprising up to 80% of the documentation for each item*****.

“What can a museum do to guarantee that the data, information and stories added by the public would have the historical source value throughout the time in the future? … While recording and storing information, we must also record and store the background data of the information to each description: the person who enters it; the time, the place and the situation of entering); and all the additional sources used in the description.”

Description creation for museum objects in a digital environment. Co-creation – Kaie Jeeser (UH – University Heritage) – https://universityheritage.eu/en/description-creation-for-museum-objects-in-a-digital-environment-co-creation/

Museums and other cultural memory institutions can reshape their role in modern society, becoming crucial hubs for addressing and solving key challenges in digital culture. To do so effectively, it’s vital for museums and their experts to leverage digital technology and internet connectivity in alignment with their technical and institutional goals.

We will persist in our experimentation at IBRAM, with plans to launch the Mastodon instance “social.museus.gov.br” next week. Our motivation stems from the aspiration to build a social network infrastructure capable of accommodating public interest memory institutions. Here, data from museums’ interactions with their audience will be preserved, serving as a digital collection for research purposes.

Also, it will be exciting to have the chance to configure the Fediverse’s social networking features to facilitate dialogue on updating the documentation of decolonized collections. We’ll keep you updated on this process here on the blog.

References:

- (*) “World culture, world history, and the roles of a museum: a conceptual study of the Swedish museums of world culture, debates concerning them, and their roles in cultural politics” – Tobias Harding – https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10286632.2020.1752684

- (**) “The Connectenedness of Archives: Museums in Brazil and Europe” – Manuela Fischer e Adriana Munhoz – https://www.redalyc.org/journal/2470/247065256009/html/

- (***) Europeana Research collaborations: The National Museum of World Culture, Sweden – Pro.Europeana.Edu – https://pro.europeana.eu/page/europeana-research-collaborations-the-national-museum-of-world-culture-sweden

- (****) From the Amazon rainforest to the collections of the Museum of World Culture – Department of Historical Studies – https://www.gu.se/en/news/from-the-amazon-rainforest-to-the-collections-of-the-museum-of-world-culture

- (*****) Description creation for museum objects in a digital environment. Co-creation – Kaie Jeeser (UH – University Heritage) – https://universityheritage.eu/en/description-creation-for-museum-objects-in-a-digital-environment-co-creation/

@blog testing commenting directly from Mastodon!

@blog UAU!!!! Beautiful day in Amsterdam!!!!